Appendix III K. Peptide Mapping1

Peptide mapping is an identity test for proteins, especially those obtained by rDNA technology. It involves the chemical or enzymatic treatment of a protein resulting in the formation of peptide fragments followed by separation and identification of these fragments in a reproducible manner. It is a powerful test that is capable of identifying almost any single amino acid changes resulting from events such as errors in the reading of complementary DNA (cDNA) sequences or point mutations. Peptide mapping is a comparative procedure because the information obtained, compared to a reference substance similarly treated, confirms the primary structure of the protein, is capable of detecting whether alterations in structure have occurred, and demonstrates process consistency and genetic stability. Each protein presents unique characteristics which must be well understood so that the scientific and analytical approaches permit validated development of a peptide map that provides sufficient specificity.

This chapter provides detailed assistance in the application of peptide mapping and its validation to characterise the desired protein, to evaluate the stability of the expression construct of cells used for recombinant DNA products and to evaluate the consistency of the overall process, to assess product stability as well as to ensure the identity of the protein, or to detect the presence of protein variant.

Peptide mapping is not a general method, but involves developing specific maps for each unique protein. Although the technology is evolving rapidly, there are certain methods that are generally accepted. Variations of these methods will be indicated, when appropriate, in specific monographs.

A peptide map may be viewed as a fingerprint of a protein and is the end product of several chemical processes that provide a comprehensive understanding of the protein being analysed. 4 principal steps are necessary for the development of the procedure: isolation and purification of the protein, if the protein is part of a formulation; selective cleavage of the peptide bonds; chromatographic separation of the peptides; and analysis and identification of the peptides. A test sample is digested and assayed in parallel with a reference substance. Complete cleavage of peptide bonds is more likely to occur when enzymes such as endoproteases (e.g., trypsin) are used, instead of chemical cleavage reagents. A map must contain enough peptides to be meaningful. On the other hand, if there are too many fragments, the map might lose its specificity because many proteins will then have the same profiles.

ISOLATION AND PURIFICATION

Isolation and purification are necessary for analysis of bulk drugs or dosage forms containing interfering excipients and carrier proteins and, when required, will be specified in the monograph. Quantitative recovery of protein from the dosage form must be validated.

SELECTIVE CLEAVAGE OF PEPTIDE BONDS

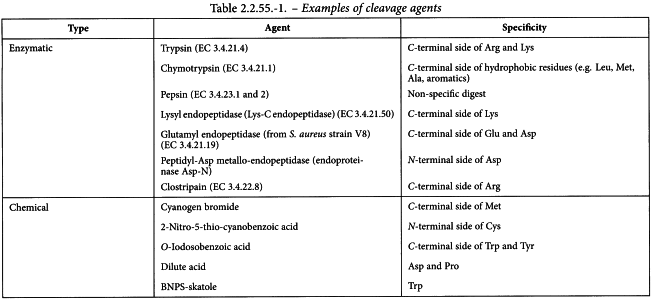

The selection of the approach used for the cleavage of peptide bonds will depend on the protein under test. This selection process involves determination of the type of cleavage to be employed, enzymatic or chemical, and the type of cleavage agent within the chosen category. Several cleavage agents and their specificity are shown in Table 2.2.55.-1. This list is not all-inclusive and will be expanded as other cleavage agents are identified.

Pretreatment of sample

Depending on the size or the configuration of the protein, different approaches in the pretreatment of samples can be used. If trypsin is used as a cleavage agent for proteins with a molecular mass greater than 100 000 Da, lysine residues must be protected by citraconylation or maleylation; otherwise, too many peptides will be generated.

Pretreatment of the cleavage agent

Pretreatment of cleavage agents, especially enzymatic agents, might be necessary for purification purposes to ensure reproducibility of the map. For example, trypsin used as a cleavage agent will have to be treated with tosyl-l-phenylalanine chloromethyl ketone to inactivate chymotrypsin. Other methods, such as purification of trypsin by high performance liquid chromatography (HPLC) or immobilisation of enzyme on a gel support, have been successfully used when only a small amount of protein is available.

Pretreatment of the protein

Under certain conditions, it might be necessary to concentrate the sample or to separate the protein from excipients and stabilisers used in formulation of the product, if these interfere with the mapping procedure. Physical procedures used for pretreatment can include ultrafiltration, column chromatography and lyophilization. Other pretreatments, such as the addition of chaotropic agents (e.g. urea) can be used to unfold the protein prior to mapping. To allow the enzyme to have full access to cleavage sites and permit some unfolding of the protein, it is often necessary to reduce and alkylate the disulfide bonds prior to digestion.

Digestion with trypsin can introduce ambiguities in the peptide map due to side reactions occurring during the digestion reaction, such as non-specific cleavage, deamidation, disulfide isomerisation, oxidation of methionine residues, or formation of pyroglutamic groups created from the deamidation of glutamine at the N-terminal side of a peptide. Furthermore, peaks may be produced by autohydrolysis of trypsin. Their intensities depend on the ratio of trypsin to protein. To avoid autohydrolysis, solutions of proteases may be prepared at a pH that is not optimal (e.g. at pH 5 for trypsin), which would mean that the enzyme would not become active until diluted with the digest buffer.

Establishment of optimal digestion conditions

Factors that affect the completeness and effectiveness of digestion of proteins are those that could affect any chemical or enzymatic reactions.

pH of the reaction milieu The pH of the digestion mixture is empirically determined to ensure the optimisation of the performance of the given cleavage agent. For example, when using cyanogen bromide as a cleavage agent, a highly acidic environment (e.g. pH 2, formic acid) is necessary; however, when using trypsin as a cleavage agent, a slightly alkaline environment (pH 8) is optimal. As a general rule, the pH of the reaction milieu must not alter the chemical integrity of the protein during the digestion and must not change during the course of the fragmentation reaction.

Temperature A temperature between 25 °C and 37 °C is adequate for most digestions. The temperature used is intended to minimise chemical side reactions. The type of protein under test will dictate the temperature of the reaction milieu, because some proteins are more susceptible to denaturation as the temperature of the reaction increases. For example, digestion of recombinant bovine somatropin is conducted at 4 °C, because at higher temperatures it will precipitate during digestion.

Time If sufficient sample is available, a time course study is considered in order to determine the optimum time to obtain a reproducible map and avoid incomplete digestion. Time of digestion varies from 2 h to 30 h. The reaction is stopped by the addition of an acid which does not interfere in the map or by freezing.

Amount of cleavage agent used Although excessive amounts of cleavage agent are used to accomplish a reasonably rapid digestion time (i.e. 6-20 hours), the amount of cleavage agent is minimised to avoid its contribution to the chromatographic map pattern. A protein to protease ratio between 20:1 and 200:1 is generally used. It is recommended that the cleavage agent is added in 2 or more stages to optimise cleavage. Nonetheless, the final reaction volume remains small enough to facilitate the next step in peptide mapping, the separation step. To sort out digestion artifacts that might interfere with the subsequent analysis, a blank determination is performed, using a digestion control with all the reagents, except the test protein.

CHROMATOGRAPHIC SEPARATION

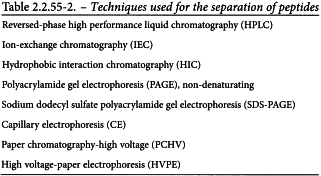

Many techniques are used to separate peptides for mapping. The selection of a technique depends on the protein being mapped. Techniques that have been successfully used for separation of peptides are shown in Table 2.2.55-2. In this section, a most widely used reversed-phase HPLC method is described as one of the procedures of chromatographic separation.

The purity of solvents and mobile phases is a critical factor in HPLC separation. HPLC-grade solvents and water that are commercially available, are recommended for reversed-phase HPLC. Dissolved gases present a problem in gradient systems where the solubility of the gas in a solvent may be less in a mixture than in a single solvent. Vacuum degassing and agitation by sonication are often used as useful degassing procedures. When solid particles in the solvents are drawn into the HPLC system, they can damage the sealing of pump valves or clog the top of the chromatographic column. Both pre- and post-pump filtration is also recommended.

Chromatographic column

The selection of a chromatographic column is empirically determined for each protein. Columns with 10 nm or 30 nm pore size with silica support can give optimal separation. For smaller peptides, octylsilyl silica gel for chromatography R (3-10 µm) and octadecylsilyl silica gel for chromatography R (3-10 µm) column packings are more efficient than butylsilyl silica gel for chromatography R (5-10 µm).

Solvent

The most commonly used solvent is water with acetonitrile as the organic modifier to which not more than 0.1 per cent trifluoroacetic acid is added. If necessary, add propyl alcohol or isopropyl alcohol to solubilise the digest components, provided that the addition does not unduly increase the viscosity of the components.

Mobile phase

Buffered mobile phases containing phosphate are used to provide some flexibility in the selection of pH conditions, since shifts of pH in the 3.0-5.0 range enhance the separation of peptides containing acidic residues (e.g. glutamic and aspartic acids). Sodium or potassium phosphates, ammonium acetate, phosphoric acid at a pH between 2 and 7 (or higher for polymer-based supports) have also been used with acetonitrile gradients. Acetonitrile containing trifluoroacetic acid is used quite often.

Gradient

Gradients can be linear, nonlinear, or include step functions. A shallow gradient is recommended in order to separate complex mixtures. Gradients are optimised to provide clear resolution of 1 or 2 peaks that will become ″marker″ peaks for the test.

Isocratic elution

Isocratic HPLC systems using a single mobile phase are used on the basis of their convenience of use and improved detector responses. Optimal composition of a mobile phase to obtain clear resolution of each peak is sometimes difficult to establish. Mobile phases for which slight changes in component ratios or in pH significantly affect retention times of peaks in peptide maps must not be used in isocratic HPLC systems.

Other parameters

Temperature control of the column is usually necessary to achieve good reproducibility. The flow rates for the mobile phases range from 0.1-2.0 mL/min, and the detection of peptides is performed with a UV detector at 200-230 nm. Other methods of detection have been used (e.g. post-column derivatisation), but they are not as robust or versatile as UV detection.

Validation

This section provides an experimental means for measuring the overall performance of the test method. The acceptance criteria for system suitability depend on the identification of critical test parameters that affect data interpretation and acceptance. These critical parameters are also criteria that monitor peptide digestion and peptide analysis. An indicator that the desired digestion endpoint has been achieved is shown by comparison with a reference standard, which is treated in the same manner as the test protein. The use of a reference substance in parallel with the test protein is critical in the development and establishment of system suitability limits. In addition, a chromatogram is included with the reference substance for additional comparison purposes. Other indicators may include visual inspection of protein or peptide solubility, the absence of intact protein, or measurement of responses of a digestion-dependent peptide. The critical system suitability parameters for peptide analysis will depend on the particular mode of peptide separation and detection and on the data analysis requirements.

When peptide mapping is used as an identification test, the system suitability requirements for the identified peptides cover selectivity and precision. In this case, as well as when identification of variant protein is done, the identification of the primary structure of the peptide fragments in the peptide map provides both a verification of the known primary structure and the identification of protein variants by comparison with the peptide map of the reference substance for the specified protein. The use of a digested reference substance for a given protein in the determination of peptide resolution is the method of choice. For an analysis of a variant protein, a characterised mixture of a variant and a reference substance can be used, especially if the variant peptide is located in a less-resolved region of the map. The index of pattern consistency can be simply the number of major peptides detected. Peptide pattern consistency can be best defined by the resolution of peptide peaks. Chromatographic parameters, such as peak-to-peak resolution, maximum peak width, peak area, peak tailing factors, and column efficiency, may be used to define peptide resolution. Depending on the protein under test and the method of separation used, single peptide or multiple peptide resolution requirements may be necessary.

The replicate analysis of the digest of the reference substance for the protein under test yields measures of precision and quantitative recovery. Recovery of the identified peptides is generally ascertained by the use of internal or external peptide standards. The precision is expressed as the relative standard deviation (RSD). Differences in the recovery and precision of the identified peptides are to be expected; therefore, the system suitability limits will have to be established for both the recovery and the precision of the identified peptides. These limits are unique for a given protein and will be specified in the individual monograph.

Visual comparison of the relative retentions, the peak responses (the peak area or the peak height), the number of peaks, and the overall elution pattern is completed initially. It is then complemented and supported by mathematical analysis of the peak response ratios and by the chromatographic profile of a 1:1 (V/V) mixture of sample and reference substance digest. If all peaks in the sample digest and in the reference substance digest have the same relative retentions and peak response ratios, then the identity of the sample under test is confirmed.

If peaks that initially eluted with significantly different relative retentions are then observed as single peaks in the 1:1 mixture, the initial difference would be an indication of system variability. However, if separate peaks are observed in the 1:1 mixture, this would be evidence of the nonequivalence of the peptides in each peak. If a peak in the 1:1 mixture is significantly broader than the corresponding peak in the sample and reference substance digest, it may indicate the presence of different peptides. The use of computer-aided pattern recognition software for the analysis of peptide mapping data has been proposed and applied, but issues related to the validation of the computer software preclude its use in a compendial test in the near future. Other automated approaches have been used that employ mathematical formulas, models, and pattern recognition. Such approaches are, for example, the automated identification of compounds by IR spectroscopy and the application of diode-array UV spectral analysis for identification of peptides. These methods have limitations due to inadequate resolutions, co-elution of fragments, or absolute peak response differences between reference substance and sample digest fragments.

The numerical comparison of the peak retention times and peak areas or peak heights can be done for a selected group of relevant peaks that have been correctly identified in the peptide maps. Peak areas can be calculated using 1 peak showing relatively small variation as an internal reference, keeping in mind that peak area integration is sensitive to baseline variation and likely to introduce error in the analysis. Alternatively, the percentage of each peptide peak height relative to the sum of all peak heights can be calculated for the sample under test. The percentage is then compared to that of the corresponding peak of the reference substance. The possibility of auto-hydrolysis of trypsin is monitored by producing a blank peptide map, that is, the peptide map obtained when a blank solution is treated with trypsin.

The minimum requirement for the qualification of peptide mapping is an approved test procedure that includes system suitability as a test control. In general, early in the regulatory process, qualification of peptide mapping for a protein is sufficient. As the regulatory approval process for the protein progresses, additional qualifications of the test can include a partial validation of the analytical procedure to provide assurance that the method will perform as intended in the development of a peptide map for the specified protein.

ANALYSIS AND IDENTIFICATION OF PEPTIDES

This section gives guidance on the use of peptide mapping during development in support of regulatory applications.

The use of a peptide map as a qualitative tool does not require the complete characterisation of the individual peptide peaks. However, validation of peptide mapping in support of regulatory applications requires rigorous characterisation of each of the individual peaks in the peptide map. Methods to characterise peaks range from N-terminal sequencing of each peak followed by amino acid analysis to the use of mass spectroscopy (MS).

For characterisation purposes, when N-terminal sequencing and amino acids analysis are used, the analytical separation is scaled up. Since scale-up might affect the resolution of peptide peaks, it is necessary, using empirical data, to assure that there is no loss of resolution due to scale-up. Eluates corresponding to specific peptide peaks are collected, vacuum-concentrated, and chromatographed again, if necessary. Amino acid analysis of fragments may be limited by the peptide size. If the N-terminus is blocked, it may need to be cleared before sequencing. C-terminal sequencing of proteins in combination with carboxypeptidase and matrix-assisted laser desorption ionisation coupled to time-of-flight analyser (MALDI-TOF) can also be used for characterisation purposes.

The use of MS for characterisation of peptide fragments is by direct infusion of isolated peptides or by the use of on-line LC-MS for structure analysis. In general, it includes electrospray and MALDI-TOF-MS, as well as fast-atom bombardment (FAB). Tandem MS has also been used to sequence a modified protein and to determine the type of amino acid modification that has occurred. The comparison of mass spectra of the digests before and after reduction provides a method to assign the disulfide bonds to the various sulfydryl-containing peptides.

If regions of the primary structure are not clearly demonstrated by the peptide map, it might be necessary to develop a secondary peptide map. The goal of a validated method of characterisation of a protein through peptide mapping is to reconcile and account for at least 95 per cent of the theoretical composition of the protein structure.